Optional, but for those who like their comedies with a prologue, please see Part 1: A Summer of Good Intentions and Bad Attention.

It began, as all midlife revelations do in the year 2025, with a YouTube thumbnail: a woman in Santorini holding The Bell Jar like a wine glass, promising that travel had healed her reading life. The Good Reader clicked. And clicked again. And an hour later, algorithmically enlightened and fully caffeinated, he arrived at a conclusion so bold, so unearned, so obviously doomed that it could only be his: the problem was place. Not him. Never him. His unread summer was not a failure of will, attention, he told himself. It was environmental. He had been trying to read in the same stale corners where he paid bills, ignored text messages, and watched seventeen-minute videos on decluttering without decluttering. But what if he moved? What if, like the travel gods and booking apps and shimmering people of Instagram had foretold, a change in scenery could change everything?

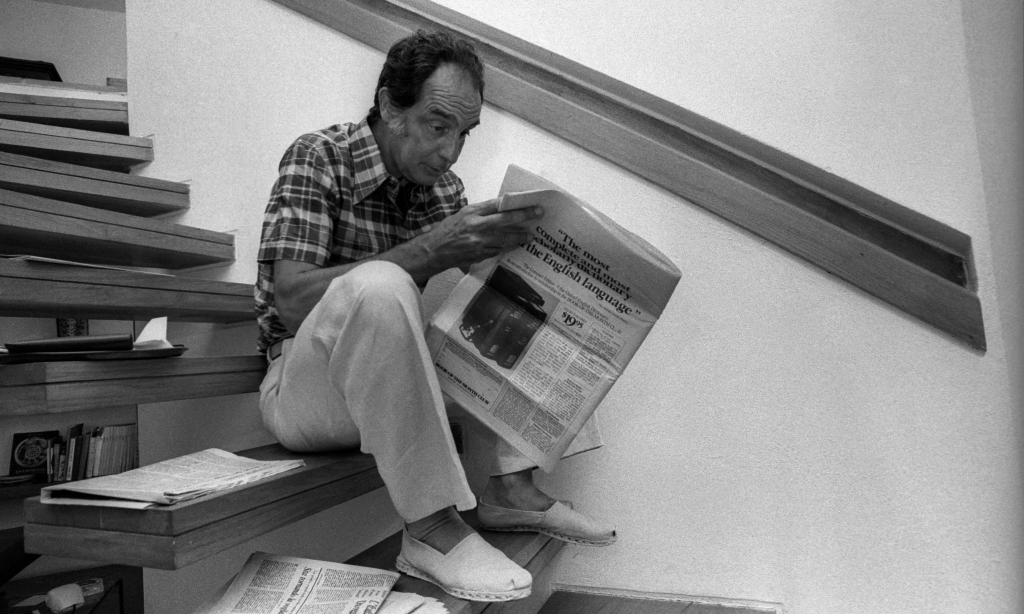

And so, delirious with purpose, he packed his bags, not with socks or chargers, but with intentions. He would read where the air smelled different. He would annotate in cafes with wooden tables and unobtrusive jazz. He would become the kind of man who reads under foreign skies. Never mind that Austen never left Hampshire, Dickens barely crossed the Channel, and Tolstoy, that snowy colossus, wrote War and Peace without once visiting a curated riad in Marrakesh. The Good Reader was not interested in historical precedent. He was interested in possibility. In curated stillness. In Airbnb silence. In the slow-motion footage of himself turning a page while a tram passed behind him in Lisbon.

And so he departed, hopeful, unread, and chronically online, to chase literature across oceans. His first stop: Chennai.

So the Good Reader’s summer pilgrimage began in Chennai, that humid furnace of temples, traffic, and family obligations, where he arrived on a British Airways flight carrying not only luggage but also a dozen hardcovers. As he stumbled out of immigration, two taxi drivers instantly materialized, each shouting competing truths: one quoted 1,400 rupees, the other 700, about $17 versus $8, both assuring him with priestly conviction that their fare alone contained salvation. There was a philosophical question in it. Was the Good Reader worth double? Or was he, as he feared, the kind of man who would always choose the cheaper cab and therefore the cheaper fate? Before he could answer, the crowd surged, horns blared, and Chennai wrapped him in its dense, sweaty embrace.

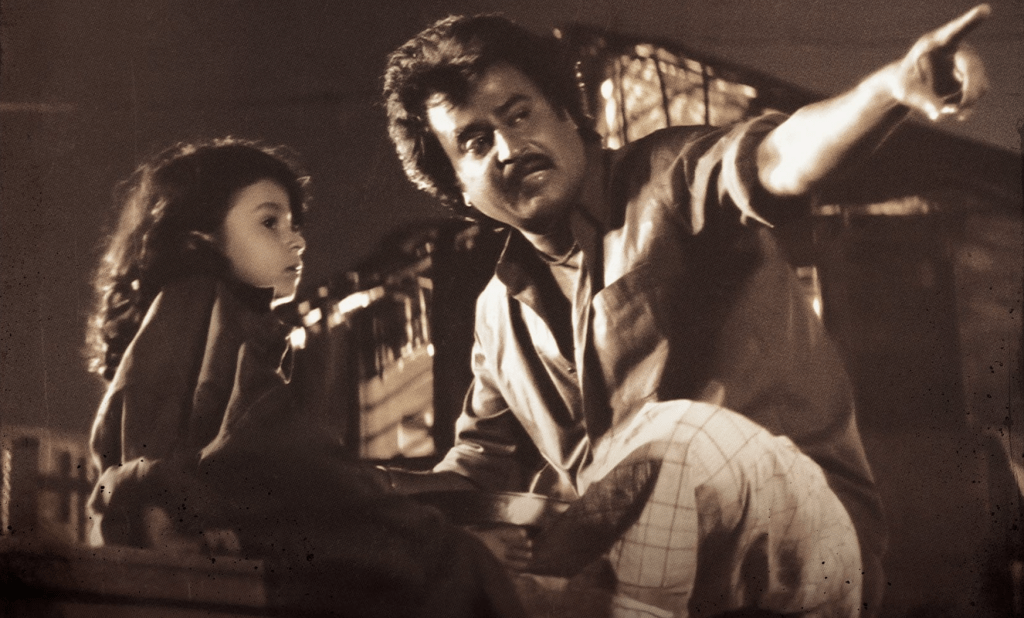

The very first thing he read in India was Kanni Theevu, the serialized comic strip that has been running for sixty-three years in the Dina Thanthi newspaper. Episode #23,193. Yes, twenty-three thousand one hundred and ninety-three. That’s more than Proust, Balzac, and Dickens combined. This morning’s installment featured Sindbad, the once-classic adventurer, now inexplicably conscripted into something resembling a Rajamouli battle scene, flying about on golden birds with arrows sticking out of their feathers. It was magnificent nonsense, and the Good Reader thought: If this is literature in Chennai, I can stop worrying. The city is already reading for me.

It was the month of Aadi, when the goddesses descend from their sanctums and erupt onto the roads in twelve-foot banners, neon-outlined and serial-lit like cosmic billboards. Lakshmi gleamed beside traffic lights, Mariamman beamed over pharmacies, and Durga’s lion snarled above autorickshaws. Twice, in peak evening traffic, his car was engulfed by ritual throngs; and both times, in an act of supreme kindness, the crowd parted, waving him forward. The result was an accidental drive-thru darshan. For a surreal instant he found himself peering straight through the temple doors at the deity herself, chauffeured to revelation without leaving the back seat.

Day One was meant for buying local books. He would buy Indian magazines and dailies to read in India. He returned with India Today, The Hindu, a yellowing Ananda Vikatan, and, because the kiosk man smirked, Vogue India. He stacked them reverently, and prepared to read. But first, a mini tiffin for breakfast. And the pongal, golden, molten, ghee-laden, destroyed him. He collapsed into a seven-hour carb coma. When he woke, three aunties, two uncles, and a cousin he hadn’t seen since 1999 had materialized with more food. Reading was postponed, indefinitely, to the afterlife.

And yet, amid the assaults of ghee, he always found salvation in filter coffee. The slow drip of decoction, brewed like a lab experiment and frothed into steel tumblers, became his truest text. Each cup promised twenty pages of progress; instead, it delivered twenty minutes of jittery pacing and long essays to himself about what he would read later. Still, he drank cup after cup, a pilgrim in the Church of Decoction.

The days blurred: temples, traffic, relatives, food. Chennai was a city under permanent renovation, each street dug up, each corner sprouting a Metro Train pillar, as if the city were sacrificing the present so some future generation could glide smoothly forty years hence. Every cab ride was meant to be his silent reading hour, but instead became a rolling seminar: Vijay’s political entry, the price of tomatoes, whether cricket collapses were fate or foolishness. He nodded gravely, muttered “Ah, correct, correct,” and held his book like a tragicomic prop.

Once, he managed a walk. From Bazullah Road to G.N. Chetty Road, past Vani Mahal, he crossed Sangeetha and Geetham, two restaurants that had split like quarreling siblings, now competing with identical menus. At Sangeetha he ordered coffee; at Geetham, tea. Both tasted excellent, both arrived boiling, both sugared beyond mercy. The difference was academic: one was called tea, the other coffee. That walk, probably the longest he managed in Chennai, grounded him. Elsewhere, walking was impossible. KK Nagar was a chaos of potholes, encroached pavements, snarling traffic, and an absurd street-war over stray dogs. People shouted, groups split, alliances shifted. Our Good Reader, wisely, stayed neutral, knowing either side might bite.

He sought books again. The Tamil bookshop offered him little, yet staring at the rows of unfamiliar names he chastised himself. He stared at the Tamil titles, feeling the weight of his own ambition. Was he chasing literature, or just running from himself? He must change his attitude, return to Tamil contemporary writing, discover something beyond Sujatha’s science fiction and Ashokamitran’s humble novels. Driving past their houses, he remembered them with reverence, along with Cho’s satire and Jayakanthan’s radical prose.

On a drive to Kanchipuram, the so-called city of a thousand temples, he found that nearly all of them were undergoing renovation. Every gopuram was covered in scaffolding, slathered in a coat of ritual yellow fabric. Shiva, Vishnu, all seemed to have conspired to hold a citywide consecration clearance sale. The gods were still eternal, but their towers looked like construction projects from an overambitious municipal plan.

He tried English bookstores in malls. He tried. But the shelves carried The Da Vinci Code, Fifty Shades, GRE prep guides from 2011. It looked like US Airport bookstores in exile, only dustier.

He sighed, bought yet another tote bag, and carried it to Kapaleeshwarar Temple, convinced that perhaps the gods would grant him a chapter if he only read in their presence. He settled cross-legged in a corner with his book, tote bag beside him like a loyal but useless squire. Almost immediately the temple loudspeakers roared to life. A man with a voice like gravel mixed with nasal syrup launched into a public sermon: simple life truths from the Thevaram, twisted into parables about grocery bills, cricket collapses, and unruly children. Every few sentences he broke into song, a thin, nasal chant of Thevaram verses that the microphone faithfully mangled and then blared for three kilometers in every direction. Each note ricocheted across the gopuram and into the Good Reader’s skull. Reading Julian Barnes was hard enough in silence; under the assault of devotional karaoke, it was impossible.

He shifted, hunting for quiet, and found a side space near the small shrine of Lord Shaniswara, where the sound was fractionally less punishing. There he discovered two temple cats playing tag among the pillars, their chase far more gripping than any plot in his unopened book. He noticed the devotees too: everyone walked in strict single file on a cemented path coated with some mysterious cooling compound, as if the temple floor had become a game board where stepping outside the squares meant instant disqualification. Curious, he sat down to observe, but within three seconds the stored heat of the ancient stone rushed straight through his dhoti and into his spine. He sprang up like a man electrocuted, though he later told himself it was all deliberate.

The real reason for his sudden leap was more persuasive: beneath the gopuram, volunteers were distributing hot puliyodharai in little cups made from pressed dry leaves. The smell alone collapsed his literary ambitions. He abandoned the shrine, the cats, the tote bagged books, and joined the throng, shoveling down the tangy tamarind rice with manic devotion. Once was not enough. He returned for a second serving, standing barefoot among strangers, cheeks bulging with holy carbs, taste buds singing Yaar Yaar Sivam, off-key but bliss-drunk. The book, once again, never left the bag.

Even Wi-Fi mocked him. In his bedroom, the signal wheezed like a dying harmonium. To catch a bar, he shuffled into the living room, where serials blared at max volume. He abandoned books and began reading people instead: their gossip, their WhatsApp forwards, their endless speculation about weddings. Chennai gave him not novels but serialized oral epics, complete with cliffhangers and filter coffee breaks.

Modernity added its own comedy. Swiggy, Zomato, Blinkit, Instamart delivered at such speed he suspected even literature might arrive boxed in ten minutes. It never did. Instead, always rava dosa. He ate, grateful, and stayed unread.

For variety, he tried five-star buffets. Two hotels in a week. Here he discovered India’s paradox of luxury: naans transcendent, curries mediocre, prices astronomical. Hospitality itself was the entree; waiters refilled plates like emergency responders, insisted he try aloo gobi gratin with tragic devotion, and treated him like a visiting emperor while serving dal that tasted suspiciously like dull rainy day in Seattle.

Doctor visits, too, became their own literature. His mother’s checkups resembled travel interviews: twenty minutes on Seattle’s rainy weather, five minutes on her blood pressure. Prescriptions came only from the in-house pharmacy, a plot twist nobody resisted.

And then there was first-day-first-show Rajinikanth movie. The cinema theater was temple and stadium combined: camphor, confetti, applause that bent walls. His book became a popcorn coaster, his glasses fogged from ecstasy. Reading had no chance against Rajini.

At Thiruvannamalai, the temple wasn’t a sanctuary but an ocean. Humanity surged in tidal waves; incense smoked like fog machines; chants thundered like amplifiers. To imagine pulling out Karl Ove Knausgaard was delusion. Reading here was not resistance, it was surrender, to sweat, to rhythm, to collective devotion. And then, unexpectedly, for a few minutes he forgot about tote bags, Goodreads lists, Knausgaard, all of it. He was just another body in the tide, pressed shoulder to shoulder, palms streaked with turmeric and vibhuti ash, chanting syllables he barely recognized. He was swallowed, shaken, broken open, and yet, in that surrender, he felt something astonishingly close to what he had come chasing: attention, undivided and absolute. Not on a page, but on a god glowing behind a curtain of incense.

Still, Chennai was not cruel. It engulfed him with kindness. Strangers guided him across roads. Relatives fed him as though he were a famine orphan. Doctors leaned in, curious about Seattle clouds. Goddesses glowed at intersections. The city whispered, “Don’t read me in a book. Read me directly”. It gave him sweat, gossip, ghee, coffee, neon, scaffolding, potholes, kindness. His books remained locked in their suitcase, noble tourists never stamped. The one text he read with full attention? A restaurant bill itemizing “pongal (extra ghee)” twice.

After twelve nights, which he generously rebranded as a personal Twelfth Night, the Good Reader boarded his flight. Shakespeare had banishment and disguise; he had tote bags and unopened books. Unread but faintly adored, he moved on to the next city, still incapable of finishing page one but fully committed to the sequel.

(to be continued…)

cross-posted to LinkedIn