This essay is part of the Pesum Padam – Mani Ratnam Retrospective Series and revisits Nayakan. Watch the retrospective tomorrow on youtube.

My maternal grandfather, was the most righteous man I knew. He saw the world in clean lines. You were either good or you were not. Yet for all his black-and-white convictions, there was one name he spoke of with a peculiar softness. Pettikada Rajendran. A man who, according to him, ruled Georgetown in Madras with nothing but a stare and a sly smile. My grandfather was a young bookkeeper at a textile shop in Parry’s Corner when Rajendran stopped him once on the road. “I see you every day walking to work. Keep good health,” he said. Years later, during a scuffle at a bus stop, it was Rajendran who stepped in to defuse the tension. “From that day,” my grandfather said, “we’d nod to each other in the evenings.”

Rajendran was, by most accounts, a petty criminal. But he had rules. He collected from the rich shop owners who underpaid and overworked and gave to the vendors pushed off the streets. When the police came for him one night, the entire street shut down in protest. “He was not right…. but he helped.” That answer stayed with me. It made no sense at the time. But years later, when I watched Nayakan as an adult and really watched it, I began to understand.

Velu Naicker was not a fictional fantasy. He was a distillation of hundreds of Pettikada Rajendrans. Men who rose from within broken systems and didn’t wait for justice to arrive but rearranged justice to fit their corner of the world. I may not be able to agree with them. But I understand the ache behind their choices. Perhaps Nayakan was Mani Ratnam’s way of walking closer to Pettikada Rajendran not to praise him or pardon him but to ask him gently why.

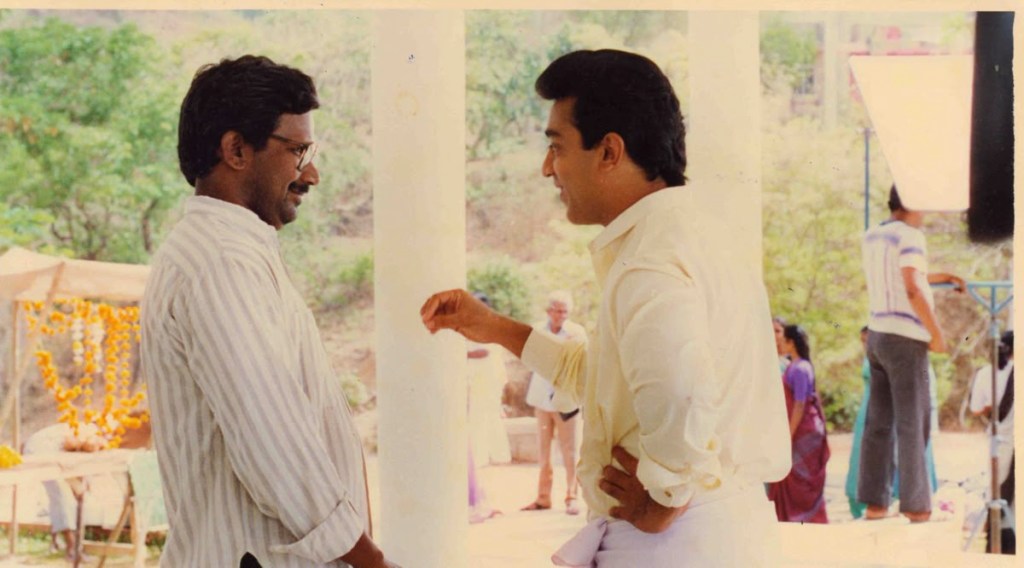

What’s most fascinating about Nayakan is how quietly it traces the anatomy of a man aging under the weight of power. It’s not a film of grand arcs or thunderous acts. It is a story told through gradual erosion. Every gain in Velu Naicker’s world is mirrored by a loss in his soul. The movie moves forward not as chapters but as scars. Five of them, if you look closely. With each personal loss, his father, his foster father, his wife, his son, and finally himself, Velu’s face changes, his posture shifts, hairline recedes and voice lowers. Kamal Haasan, in a performance that can only be described as haunted restraint, ages the character not through makeup but through emotional subtraction. You watch the man vanish piece by piece from behind his eyes.

Mani doesn’t give us a traditional rise-and-fall gangster story. He gives us a series of psychological thresholds. Each one is marked by a death and a quiet reinvention. First, the boy who sees his father beaten to death. Then, the young immigrant in Dharavi, still unsure whether to follow his foster father’s smuggling trade or escape it. Then comes the defiant firebrand, confronting police brutality head-on and marrying a girl who is forced to become a sex worker with a kind smile and godliness in her breath. Later, the matured don with oiled-back hair, glasses, and a kunguma theetral on his forehead, a man who’s learned to live with violence like it’s a second language. Finally, the elder statesman of the slums, slowed by age, undone by grief, squatting down as his grandson asks him the only question that matters. “Were you good man or bad?” That question is not just for Velu. It’s for all of us who watched him nod silently through his life, convincing ourselves that what he did was necessary, that he helped, that he meant well. But in the end, even he doesn’t know. All he can do is say “I don’t know” and disappear.

One of Mani’s most distinctive choices as a filmmaker is his ability to define his characters through absence. Not in screen time, but in what they withhold from others and from us. Velu Naicker doesn’t spend the film justifying his life. He doesn’t deliver monologues about revenge, poverty, or justice. In fact, he says very little. We are invited not into his thoughts but into his silences, which grow heavier with each passing loss. It’s in these withheld emotions that Nayakan becomes most haunting. It’s a film filled with unsaid things, and that is precisely where it derives its power.

But in a film defined by restraint, there is one moment where the dam breaks. When his daughter Charu confronts him, when she slaps Selva, his loyal right hand, and demands to know why this violence continues and why her father continues to be feared, the wound that Velu has kept stitched up for decades is finally touched. Not by a gun or a rival but by his child. Mani, the filmmaker who so often builds power through suggestion, allows this one moment of naked involuntary exposition. But even this isn’t written as exposition. It erupts naturally and uncontainably. It is one of the most human scenes in all of Mani’s cinema. Velu doesn’t argue with data or stats. He pleads with pain. “Ask the policeman who killed my father to stop. Ask the man who killed your mother to stop. Then I’ll stop.” It is in every sense a heartbreakingly reasonable justification for everything unreasonable he’s done. That’s the problem.

Because the scene doesn’t just reveal Velu’s worldview, it tempts us. It wins us over, and we don’t want to be won. We want to judge him. But Mani makes it nearly impossible. His staging, Kamal’s staggering restraint-turned-implosion, the camera’s refusal to cut away, it drags us to the very place we’ve been avoiding: empathy towards Velu. Not the kind we feel good about. This is complicated and uncomfortable empathy. You understand the man and how he got here. You even, for a second, believe he had no other choice. That’s the scariest part. You forget your moral compass just long enough to see his.

When I first watched Nayakan, I was ten. It was just another Kamal film, one of the quieter ones, the darker ones, the grown-up ones. I didn’t understand much. I liked the songs, especially Nila Adhu Vaanaththumele, which had a folk beat to it. But what I remember most isn’t Kamal, Mani, or the myth of Velu Naicker. It’s a boy, a mentally challenged boy, the son of Police Inspector Kelkar, the man Velu had killed. The boy comes to Velu, unaware, and says “Mera baba mar gaya.” There was something about that, the absence of the grief and logic, the sheer innocence of it, that broke me. Mani has always known how to write children with unsettling honesty. They don’t act like film children. They act like they wandered in from real life. In that moment, Mera baba mar gaya felt more devastating than any violence in the movie.

Of course, back then, there were things I didn’t understand. When Velu breaks down after his son’s death, crying in that contorted way, I remember people calling it overacting, the same way they accused Sivaji Ganesan, a claim my father refused to accept. I grew up to love them both, Sivaji and Kamal, and to utterly detest the word overacting. Sometimes, when emotion is too big for the body to hold, it spills out in strange, ugly, beautiful shapes. That’s what Kamal did in that scene. Later, it was my father again who pointed me toward Andhi Mazhai Megam. He’d worked in Bombay in his early years, and the song made him nostalgic in a way he didn’t often allow himself to be. He said it was beautiful, just that. He was right. It is my favorite song from the film now, not Nee Oru Kaadhal Sangeetham, though I love that too, but Andhi Mazhai Megam, with its circular camera movements, its raw rain-soaked holi colors, and that swirling dance of joy and defiance. I only found out later that it wasn’t even scored by Ilaiyaraaja himself but by someone under his guidance. Yet it carried his mood and rhythm.

Today, watching Nayakan as an adult, after reading Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, after watching Coppola’s films countless times, after enduring a dozen Indian remakes, tributes, and loose inspirations, I’m convinced that Nayakan remains the most powerful Indian adaptation of that narrative. It is not just about grounding the story in Indian soil. It is about rebuilding the story entirely in our language, in our slums, under our street lights. Mani didn’t copy the Godfather. He refitted it and re-imagined it through the lens of Varadaraja Mudaliar, through the locales of Bombay, through the emotional currency of loss and obligation. Yes, Ram Gopal Varma’s Sarkar is a compelling attempt. Others have come and gone. But Nayakan still towers above them because it doesn’t apologize for being an adaptation.

For all the brilliance in the screenplay, for all the haunting silences and mythic structure, for all of Kamal’s near-perfect performance, to me, the true hero of Nayakan is P. C. Sreeram. The look of this film, the tonal architecture of it, is unlike anything made before it or since. Watching Nayakan is like looking at a photograph by Ansel Adams, where the dodge and burn, the highlight and the hush, can’t be replicated, only revered. What Adams did to Yosemite, P.C. did to Bombay. There is no other Indian film that looks like it, and I doubt there ever will be.

“We wanted to use a technique calling ‘flashing’ to reduce the colors. I had another idea. I wanted to give the film a ‘period’ look. But ‘flashing’ would have been expensive. So while grading, I played with the analyser to keep the colour to the minimum. Since we print on different negatives, there is no consistency. For the interiors, I decided on top lights which mellow the lights but increase the contrast. What I did with the analyser was only 2 per cent. The rest was achieved by the sets, the costumes, and lighting.¹⁴

P.C Sreeram about Nayakan’s period film look in Cinema of Interupptions

Both Agni Natchathiram and Nayakan were shot nearly back-to-back, yet Nayakan carries the mood like a stormcloud. The chiaroscuro, the glow off utensils and rain-soaked concrete, the 35mm intimacy, was pure cinematography gold. There is a shot when the lens widens, in that stunning zoom-out of Velu and Neela at the Gateway of India in Nee Oru Kaadhal Sangeetham. That shot alone made me fall in love with the camera. I couldn’t stop rewinding. I didn’t even know what telephoto lenses were, but I knew magic when I saw it.

If P. C. Sreeram was peaking with light and shadow, then Ilaiyaraaja, by contrast, was only just beginning to explore the emotional terrain he would later master with Mani Ratnam. Their partnership would peak with Thalapathi, their final collaboration. But in Nayakan, something raw, unfiltered, and extraordinary was already taking shape.

This was Ilaiyaraaja’s 400th film, and you could feel it. Thenpandi Cheemayile, with its aching voice and village lament, has rightly entered the bloodstream of Tamil cinema. But for me, the true moment was the moment between Velu and Neela in the brothel room. The camera glides gently around the bed’s mosquito netting, and the POV toggles, first Neela looking at Velu, then Velu at Neela. The music enters like a whisper circling each other just as these two broken people begin to recognize something fragile between them. Just like that, Mani, Raja, and PC find perfect rhythm.

Somewhere in the late 1990s or early 2000s, I stumbled into a Chennai theatre, maybe Jayapradha or Woodlands Symphony, to watch a screening of Govind Nihalani’s Ardh Satya. I knew nothing about it, except that Nihalani had directed Drohkaal, which Kamal had remade into Kuruthipunal, a film I admired, incidentally directed by P. C. Sreeram. I went in out of curiosity and came out changed. Ardh Satya was raw, rustic, and emotionally feral. It dealt with the same city, the same systemic rot, the same burden of rage that Nayakan would explore but from the other side of the badge. To this day, I can’t help but feel that its fingerprints are all over Nayakan, not in plot but in tone and texture, in the way men collapse under the weight of doing what they believe is right.

Some call Nayakan the peak of Mani’s career. I don’t. I see it as his first masterpiece, the one that announced not just a voice but a vocabulary. This was the film that drew a perfect line across Tamil cinema, before Nayakan and after. It stood dead center between commercial mass appeal and artistic ambition. A film with no full-length comedy track, no conventional heroism, yet it entertained, moved, and stayed. It made space for quiet and asked questions about power, loyalty, and what a man is allowed to become when the world gives him no choice. Mani would ask these questions again in Thalapathi, Guru and Raavanan each time pushing the edges of heroism further into shadow.

But this was where it began. Nayakan wasn’t just the start of a directorial journey but the blueprint for a generation of filmmakers who wanted to believe that you could do both, tell a story that mattered and pack the theaters.

Velu Naicker was not the hero we asked for. But for a broken world in a broken time, maybe he was the only one who showed up.

Leave a comment