This essay is part of the Pesum Padam – Mani Ratnam Retrospective Series and revisits Thalapathi. Watch the retrospective on youtube.

Shakespeare wrote three great tragedies, Hamlet, Macbeth, and King Lear. The last of these, a bleak study on age, inheritance, and madness, was reimagined by Akira Kurosawa into Ran, a Japanese war epic where a once mighty patriarch walks away from the burning palace he built, reduced to ash by his own choices. Many centuries earlier in India, another sprawling epic, the Mahabharata, had explored, among other major themes, the same questions of loyalty, fate, and the human cost of power.

I thought of both these stories while rewatching Thalapathi, Mani Ratnam’s 1991 interpretation of the Mahabharata through the eyes of its most wounded soul, Karna. Unlike Ran, this film opens not in a palace, but on a dirt path in a nameless village. A girl arrives on a bullock cart, heavily pregnant and barely fourteen. The year is 1959. It is the festival of Bhogi, when people discard the old to welcome the new. But this girl isn’t discarding an old sari or a broken stove. She’s discarding her future. She gives birth in a wooded patch and, in shame, places her child in a goods train. A newborn, wrapped in yellow cloth, left among sacks of grain. As the train rumbles into the sepia night, the girl runs behind it, too late.

I was thirteen the first time I saw Thalapathi. I didn’t know this was a retelling of the Karna story. I didn’t even know what Mahabharata really meant, other than that it was one of those stories they showed on Doordarshan on Sunday mornings, narrated slowly in Hindi-laced Tamil.

Karna, the Mahabharata’s tragic warrior, was a child born to royalty but abandoned at birth, raised by a charioteer’s family, and ultimately bound by loyalty to the very forces that would doom him.

In the years since, I’ve read Rajaji’s abridged Mahabharata. I’ve read Cho’s explanatory version named Mahabharatham Pesukirathu in Thuglak. I’ve spent years reading Jeyamohan’s Venmurasu, his 26,000-page epic retelling every corner of the myth. And each time, I’ve come back to Thalapathi, because Mani doesn’t just adapt the Mahabharata. He examines it with empathy and precision. He finds the fault lines and climbs inside them. Where Vyasa ends Karna’s story with silence, Mani picks up the pen and writes what comes after. Because in Thalapathi, Karna lives a little longer. Long enough to cry for his brother-friend. Long enough to love. And Mani doesn’t place him on a chariot. He puts him in a slum.

Rajinikanth’s Surya is a man born unwanted, raised without a name, and cast out by systems that insist on origin stories. He doesn’t wear divine armor. His protection is rage. His righteousness comes from hunger, his own, and that of those around him. When he meets Deva (Mammootty), the Duryodhana figure, it isn’t a moment of destiny. A wealthy man reaches across caste and class to give him what the world refused: a name, a position, and above all, loyalty. That’s the heart of Thalapathi. It’s not about Kurukeshtra war rather finding out where you belong.

I still remember watching it for the first time, one day before Diwali in 1991. A preview show at Chetpet’s Ega theatre. I was there with my friend Manikandan, two teenage boys seated somewhere in the front rows, holding our breath. And as the frames unspooled I felt something new. This wasn’t just a Rajini film. It also wasn’t just a Mani film. It was something harder to define. An epic tale carried by hand into the 90s, re-dressed in cotton shirts and bata sandals.

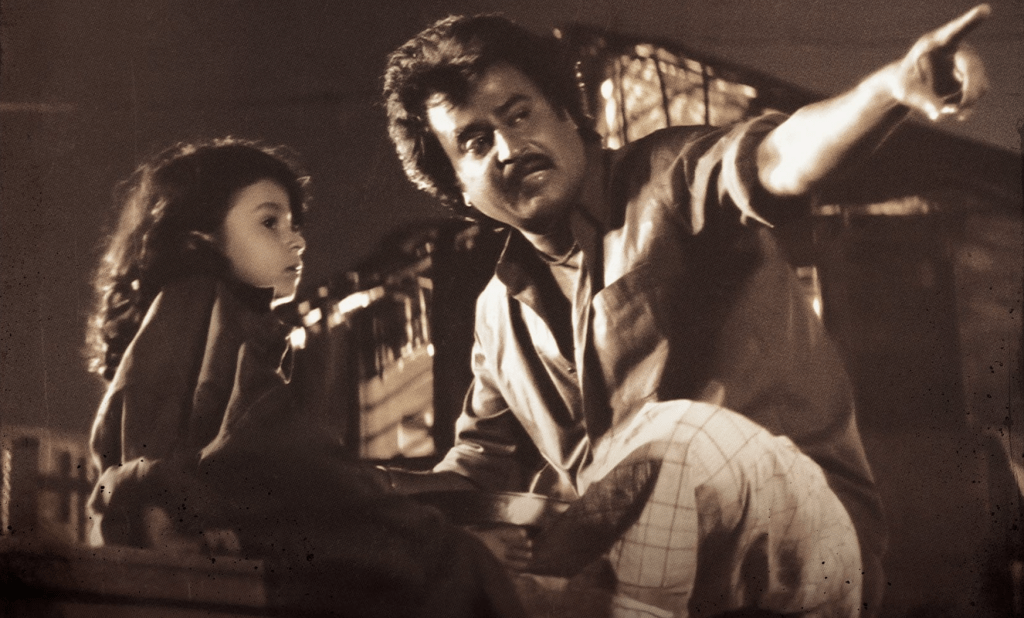

Rajinikanth had always been larger than life. But in Thalapathi, he shrinks himself. He lets Surya breathe. Gone are the punchlines and the sunglasses. Mani shoots him in slanted light and silence. You don’t see a hero. You see a man. A man who curls into his mother’s lap and whispers, “Why did you throw me away?” And that, more than the action scenes, is the moment that breaks you.

Santosh Sivan’s camera work feels both painterly and instinctive. Every frame feels carved, not shot. The close-ups are uncomfortably intimate. There’s an unforgettable overhead crane shot when Deva learns that a young girl in the slum has hanged herself. The camera floats, unblinking, as grief and fury pass between him and Surya. Mani, Raaja and Santosh create visual poetry out of moral discomfort.

And Ilaiyaraaja’s music, what can be said that hasn’t been said before? This is not just a soundtrack but also the bloodline of the film. Yamunai Aatrile is Surya’s only glimpse of peace. Chinna Thaai Aval plays like a lullaby soaked in longing. But nothing, nothing, prepares you for Sundari Kannal Oru Sethi.

A song so cinematic, it feels like a film within a film. Inspired by Kurosawa’s war sequences, the song imagines a life Surya will never live: palaces, processions, princely love. The camera sweeps through impossible luxuries. The orchestration is majestic. But at its heart, the sequence is pure hallucination. It’s a dream that will collapse into ash. This is what could have been, and what can never be.

When Deva learns that Surya’s real brother is the collector who’s trying to bring them down, he doesn’t flinch. He doesn’t feel betrayed. He feels proud. “You knew,” he says. “And still you stood by me.” The myth would have made this a moral dilemma. Mani makes it an act of love here.

Thalapathy was released on the same day as Kamal Haasan’s Guna, two titans of Tamil cinema, two of Ilaiyaraaja’s greatest soundtracks, two impossible roles played with ferocity. The audio cassette of Thalapathi was released with six different covers, a first in Indian cinema, turning it into a collector’s dream. I myself had three of them, folded like a poster.

And yet, despite all this firepower, Thalapathi is not a loud film. It is quietly devastating. It is a story about abandonment that chooses not to end in abandonment.

The final scene doesn’t unfold in a palace or a battlefield. It happens at a railway station. Arjun leaves the town with Subbalakshmi. The mother who once gave Surya away choose, this time, to stay behind, with him. The boy once discarded by a train is now embraced, and chosen.

Before I close, let me say something about Karna.

He is one of the most haunting characters in Indian literature. A child born of divine mistake, a warrior caught between blood and belonging, a man whose loyalty outlived his identity. In Vyasa’s epic, Karna is not framed as evil. He is framed as tragic. Not because he was wrong, but because he was never allowed to be right. And that, perhaps more than any other thread, is what makes his story linger, drawing playwrights, filmmakers, and novelists back to him, again and again. But while most tellings only mourn him, Mani dares to ask, what if mourning wasn’t the only option?

The Mahabharata was never wrong. It was complete, for the world it was written in. But our world has changed. So he doesn’t rewrite the Mahabharata. He brings it home to our time. And in doing that, he gives Karna something the epic never did, a life that matters. That quiet act of grace, pulling a shadowed hero into the light, may be Mani Ratnam’s most powerful ending.

Leave a comment