This essay is part of the Pesum Padam – Mani Ratnam Retrospective Series and revisits Bombay. Watch the retrospective on youtube.

It’s hard to say exactly when the house began to burn. Was it the moment Shaila Banu and Shekhar first exchanged glances on a quiet boat ride in Tirunelveli? Was it when their love, innocent and immediate, dared to cross the lines drawn by religion and community? Or did it begin much earlier, long before they ever met, in the simmering tensions of a country already primed to tear itself apart? Perhaps the fire was always there, just waiting. In Bombay, Mani Ratnam simply opens the windows and lets us see the smoke that had been gathering all along.

Bombay isn’t just a story about an interfaith marriage or communal riots. It’s about how quickly personal lives can be engulfed when the world around them starts to burn. Hatred spreads like fire from one home to the next, sometimes without warning. And yet, even in the middle of that fire, people still live. A mother still hopes her children will come home. A father still protects his family. Someone makes tea. Someone holds on to love. Bombay captures all of this in flickers and flames, and these moments, these notes, make up the soul of the film.

I don’t think I realized it the first time I watched Bombay. I was just a teenager then, but even back then it felt different. Now I see it might be Mani’s most accessible film. No, I don’t mean that in a simplified, watered-down way. It’s not a layered puzzle like Iruvar. It’s not as emotionally opaque as Kaatru Veliyidai. It’s not haunted by the abstract political messages of Dil Se. This one is direct. Straight to the heart. It hits you where you live because it feels like it’s happening next door.

When I sat down to rewatch Bombay as part of this retrospective, I was stunned by how much of it I remembered. Not just scenes, but feelings. That first glimpse of Manisha Koirala off the boat. That ridiculous disguise where Arvind Swamy wears a burqa. That rain-soaked street where a red bag becomes a symbol of pursuit. That gas cylinder explosion that tears through generations in a brief second. These aren’t just plot points. They’re lodged inside me, like memories of something I lived through, even though I didn’t.

It all begins with a glance. Just a glance across water in Tirunelveli. She arrives in a boat. He sees her. Her veil flutters in the breeze. Their eyes lock. Without a word, something is set in motion. Personal. Private. As if two strangers recognized in each other the possibility of everything.

The magic is in how Mani builds all this so quickly. I kept checking the timestamp. In just 76 minutes, he gives us a believable boy-meets-girl story in Tirunelveli, a conservative Hindu family clashing with a conservative Muslim one, a secret romance, a runaway marriage, a full relocation to Bombay, a pregnancy, a delivery of not one but two kids, a complete reset of their lives in a new city, and the emotional reality of pre-riot India. That’s not just efficient storytelling. That’s a screenwriting challenge for the ages. Try compressing all that without rushing and without losing the audience. Mani does it.

And the tone is a real feat. The first half is soft, romantic, full of rain and restraint. The second half is all tension and trauma. But the shift is seamless. You don’t feel the gears changing. You’re just pulled along, first by curiosity, then by dread. The emotional pacing is gentle, yet the narrative pacing is breakneck.

The tone shift from romance to riots is seamless on paper, but I have to admit the second half sometimes felt a bit rushed. Events escalate quickly as the city descends into chaos. While the emotional beats still land, I found myself momentarily pulled out of the film. Part of that came from recognizing the sets. The riot scenes, meant to portray the streets of Bombay, were clearly shot on the erected sets at the Campa Cola grounds in Guindy. The blinking SPIC company neon sign in the background gave it away. That single detail cracked the illusion for me. I kept wishing those sequences had been filmed on an actual location or at least built on a more convincing set. For a film that had felt so immersive and real until then, the artifice stood out.

This is also one of the few Mani Ratnam films that feels like it came from a place of urgency. You can sense it. There’s a fire under the camera. He mentioned that it was conceived as a documentary. Then it became a fiction film. Then it became Bombay. The decision to turn a child’s (or two) perspective of trauma into a full-blown family drama was instinctive. And it works.

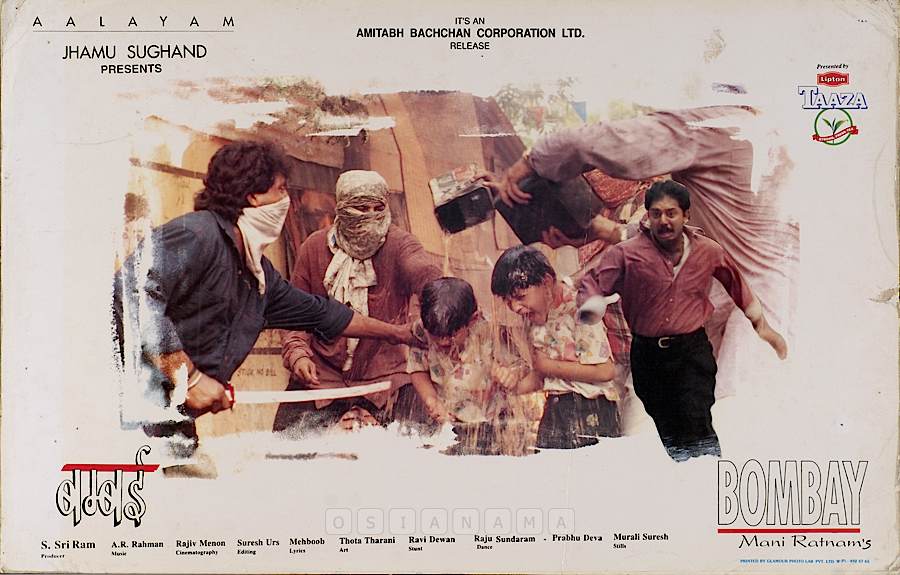

Because what could have been a dry, preachy political film becomes something far more immediate. It’s not about ideas. It’s about people. It’s about a mother standing in a burnt-down house hoping her children will find their way back. It’s about two kids, Kamal and Kabir, who get doused in kerosene while a mob tries to figure out whether they’re Hindu or Muslim. It’s about a grandfather who shows up, despite everything he said before, just to see if his son is safe. These moments matter. These are the stakes.

And the acting. Arvind Swamy, to me, finds his full form in this film. In Thalapathi, he was barely there. In Roja, he was still young. But here, he’s a man. Not a masala hero, not a tragic lover, just a man trying to hold his family together. And Manisha Koirala? How do I even start? Mani extracts something extraordinary from her. She’s not loud. She’s not performative. But she’s entirely present. The mirror scene where she catches herself smiling and calls herself mad is quiet genius. Her confrontation with Nassar, asking, not pleading, whether he’s here to split her family, is a masterclass in control.

That two-minute exchange between Shaila Banu and Narayana Pillai is the kind of scene most directors would stretch into ten. They’d load it with music, with flashbacks, with tears. Mani gives you economy. One question. One look. One line. And everything is said.

I want to talk about the music because how can you not? This might be A.R. Rahman’s most versatile early score. The Bombay theme is a lullaby pretending to be a plea. It’s classy, international, and one for the history books.

For me, the pick of the album is Kannalane. Chitra’s voice carries the whole love story in a single breath. The chemistry between Shaila Banu and Shekhar in that song is unbelievable. That notorious one-legged jump, where he steps onto the pillar and springs back in sheer joy, is the physical embodiment of a heart bursting. It’s not a dance move. It’s happiness, the kind that follows the first realization of love. That entire song is built on a foundation of simple gum-sum-gum-sum-gum-pa-chak rhythm, layered with qawwali, Mapla folk tone, and inspiration from Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. What follows is nothing short of a melodic explosion, one that hasn’t really stopped since 1995. Thirty years on, the momentum still feels like the beginning of something.

And then there is Humma Humma, also known as Antha Arabic Kadaloram. The version we first heard on cassette was already a revolution. Rahman’s own voice pulses over Middle Eastern percussion, stitched together with a rhythm that felt like Sufi rock, even though I didn’t yet have the words for it. But the film version gave us more. There was a nonsensical chant, shiganaa pagana pagana pagana bea pa that never appeared in the original album but lodged itself into my memory from the theater. Only around the 200th-day of the film, alongside Malarodu Malaringu, did that full version make it to tape. Around the 4:23 mark, the chorus begins to rise, and the song transforms into something electrifying. The Humma Humma chant arrives like a blast of air in a crowded room. It was unlike anything Tamil cinema had heard before. It became the anchor track that pulled me into the album and held me there long enough to discover the rest.

Even the editing choices here feel alive like the jittery cuts in Humma Humma, or the time-jump montages in Poovukkenna Pootu. Mani is always playing with rhythm, even visually. It’s not style. It’s syntax.

There are no perfect films, but this one comes dangerously close as a perfect Mani Ratnam film for me. It dares to compress so much pain, love, history, and humanity into one tight frame and never once loses its emotional clarity. There’s barely any comic relief, barely any “mass” moments. And yet, it was a hit. That’s the part people forget. Bombay was a critical success and a popular one. It ran for 200 days. It got banned and then reinstated in multiple countries. It was both an artistic gamble and a cultural event.

Yes, Mani lost some footage to the censors. We never saw the demolition scene as he shot it. But we still felt it through newspaper headlines, through the trembling of a mother, through the silence of a child.

Let me say this clearly: Bombay is not just Roja’s cousin, though I love that description. It’s its own creature. It stands alone because this is the film where Mani stopped flirting with politics and dove into it.

Years later, when I think of Mani’s filmography, this is the one I will point to when people ask, “Where should I start?” Not Alaipayuthey. Not Mouna Ragam. Not even Nayakan. I will point them to Bombay because this one feels real. Lived. Close.

So here it is. Bombay. Not his most complex film. Not his flashiest. But maybe his bravest.

You don’t watch Bombay for answers. You watch it to remember what it feels like when the world breaks and something tender still holds. A film that moves fast but feels deep, that captures a private ache inside a public crisis. Maybe that is what great cinema does. It reminds us that even when the world is burning, we are still just trying to find our way back to love.

Leave a comment