listen to this chapter now on youtube!

It was a truth universally acknowledged, at least by the teachers and half the student body, that his stomach had a mind of its own. On most days, it operated within acceptable parameters—growling at lunch, bubbling during chemistry—but occasionally, it would declare mutiny. This was one of those days. The ache had arrived in full force, twisting and churning in ways that suggested no mere dosa could have caused such treachery. No, this was a stomach destined for something greater, something more mysterious than a simple half-day escape from school. And though he couldn’t have known it just yet, it would take nothing less than the supernatural—perhaps even a man with snakes and a wicked gleam in his eye—to set things right. But that was for later. For now, the only thing that mattered was securing that precious outpass, the piece of paper that would grant him early release from school and enlisting the most unreliable of friends to get him home.

Algebra, it had to be said, was his natural enemy. If there was one subject capable of turning a mild, ignorable stomachache into a full-blown emergency, it was the moment Mr. Sridhar stood at the front of the class, chalk in hand, and declared with unmistakable glee, “Today, we tackle quadratic equations!” Those words alone sent a ripple through his digestive system, but things escalated when Sridhar sir, with the precision of a surgeon, began to explain a problem involving two trains, both of which seemed determined to meet on the same track, at some hypothetical speed. As Sridhar sir detailed how “x” represented something vital (though it was never quite clear what), his stomach gave an ominous rumble. And then the clincher: “And don’t forget, we have a test on this chapter in two days!”

That proclamation ratcheted up the stomachache from a gentle discomfort to a full-blown emergency. There was no way he could remain in class. If quadratic equations didn’t finish him off, the impending test surely would. The room spun slightly as Sridhar sir moved on to a second problem involving some hapless farmer attempting to divide his apples among his ungrateful cousins. Enough was enough. He would go home, take some rest, and of course, begin his revision tomorrow.

Except, naturally, he wouldn’t. That much he knew with an almost philosophical certainty as he slowly raised his hand, preparing to enact his escape plan.

Sridhar sir, deep in the throes of explaining the joys of factoring, paused mid-equation, chalk hovering like a guillotine. The class turned to look at him as he rose from his seat, clutching his side with the gravity of a man declaring his last will. He shuffled towards the front, his hand pressed against his abdomen, his face a picture of martyrdom.

“Sir, I have a stomach ache,” he whispered, contorting his features into a grimace for dramatic effect.

Sridhar sir, a veteran of many student ailments ranging from headaches to mysterious allergies, peered over his spectacles with a blend of skepticism and fatigue. “What happened?”

“I don’t know, sir,” he mumbled, his voice taking on the tone of someone revealing deep existential uncertainty. “It’s just… since last night… my tummy…”

The teacher’s eyebrow twitched. “Yes, yes, since last night. What happened?”

“I don’t know, sir,” he repeated, clearly rehearsing for a career in avoiding direct answers. “But it’s been very bad… my tummy… since last night.”

By now, the whole class was staring, and Sridhar sir, evidently realizing that no further useful information was forthcoming, sighed deeply. “Alright, alright. Go. Get to the principal’s office and… do whatever it is you need to do.”

Victory. He suppressed a grin and turned on his heel. Freedom at last—from algebra!

As he stepped into the hallway, a rush of freedom hit him—freedom from the tyranny of algebra! His hand still clutched his side for show, and he quickened his pace. The principal’s office was now the only thing standing between him and the rest of the day spent doing anything but math.

But alas, his victory was not yet assured. The outpass, tantalizingly close, was still just out of reach. There remained one final obstacle—an obstacle as formidable as any quadratic equation, perhaps even more so. The principal, Mrs. Aruna, was not a woman easily swayed by vague stomach complaints. She was a figure of towering authority, known for her no-nonsense demeanor and the way she could, with a single raised eyebrow, cause even the most confident student to rethink their entire life’s decisions. To call her strict would be an understatement—Mrs. Aruna operated by rules as rigid as a protractor, and her patience for feeble excuses was thinner than a geometry textbook.

If his performance with Mr. Sridhar had been a warm-up, this was the real test. To secure that coveted outpass, he would need every ounce of his stomach ache performance, delivered with just the right amount of pitiful desperation.

The outpass was almost his… but first, he had to face Mrs. Aruna.

The journey from the fourth floor to the principal’s office was not just a matter of walking down a staircase—it was a journey filled with existential questions, particularly when one was holding their stomach like a wounded soldier. Now, the school building had its own set of quirks. You see, in India, there’s this thing about floors. Technically, the ground floor is the first floor, but the first floor is actually the second floor, which is never not confusing. So, here he was, descending from what was technically the fourth floor but, in some strange cosmic joke, was actually the fifth floor, depending on who you asked.

As he started down the familiar square-patterned staircase, winding his way down past kids rushing up with their usual energy and teachers in saris carrying stacks of test papers, his hand firmly pressed against his perceived stomachache, he knew he had to stay in character. A grimace here, a slight stumble there—it was all part of the act. A couple of younger kids looked up at him in awe as if he was embarking on a dangerous mission. He rushed past them, his mind singularly focused on the principal’s office on the first (or second, depending on who was talking) floor.

But as he neared the gates of Mrs. Aruna’s domain, doubt crept in. Should he really go through with this? Was this going to work? After all, he had history with Mrs. Aruna. His dad had told him the tale many times: the day he got admitted to the school, back in kindergarten, the first person his dad encountered was none other than Mrs. Aruna herself—standing on these very stairs, twisting a poor student’s ear like it was a volume knob on an old radio. The kid had let out a yelp that still echoed in his dad’s mind, followed by a slap that seemed to reverberate through generations. It was an image that had stayed with him, filling his young heart with an odd combination of respect and sheer terror.

And then there were his own encounters. Speaking in Tamil during recess instead of English had cost him two whole rupees—a princely sum for a child, considering it could buy a whopping 40 lemon drops at five paisa each. “Forty lemon drops!” he thought to himself with a pang of injustice. Mrs. Aruna, as far as he was concerned, was the gatekeeper of all things cruel, unfair, and lemon-drop-depriving.

Yet, here he was again, standing on the precipice of yet another encounter with her. His stomach, which had been the star of the show until now, seemed to be second-guessing itself. Was this a good idea? Should he turn back, or was it too late? After all, he had already walked down those endless winding stairs—whether from the fourth or fifth floor, no one could be entirely sure—and there was no turning back now.

There were only two rooms in the entire school that could churn his stomach more than algebra—one was the principal’s office, and the other was the superintendent’s. The superintendent, Mr. Kalai Mani, was the “lesser principal,” the ruler of all things elementary, from kindergarten to fifth grade. After fifth grade, you graduated to the real boss—Mrs. Aruna. Both their offices had those peculiar flip-flop doors, the kind that started at hip level and sometimes at shoulder level, depending on how tall you were. They swung open with a kind of flip, like saloon doors from a western, and if you weren’t careful, you’d smack right into someone coming the other way. Fun under normal circumstances, perhaps, but these doors were located in what he liked to think of as the Yamaloka of the school—places where joy was sent for judgment and never returned.

As he entered the office, he saw Shekar sir, the school clerk, lounging behind his desk. Shekar sir, a man of few words but a master of collecting fines, looked up with an eyebrow raised.

“Why are you here?”

“Sir, I need an outpass. I have a bad stomach ache.”

His stomach, which had been hovering at a six on the pain scale, shot up to one thousand. Clutching his stomach, eyes wide, he repeated with newfound intensity, “Sir… stomach ache.”

Shekar sir blinked, unimpressed. The performance was lost on him.

“Well, shouldn’t have wasted that on him,” he thought. “That was for Mrs. Aruna.”

Shekar sir , clearly enjoying the slow pace of the day, waved a hand lazily. “The principal’s not in today. She’s on leave.”

“What?” he stammered, half-relieved, half-panicked. Mrs. Aruna wasn’t there? Good news.

“So if you need an outpass,” Shekar sir continued, “you’ll have to go to the superintendent’s room. Kalai Mani sir is in.”

His stomach flipped again—out of the frying pan, into the fire.

Sure, he didn’t have to face Mrs. Aruna today, but now he had to deal with her junior counterpart. Still, with a grimace worthy of the best Tamil cinema, he thanked Mr. Shekar and headed off towards the superintendent’s room, mentally preparing for Round Two.

Luck, it seemed, was on his side after all. As he reached Mr. Kalai Mani’s office, pushing open the familiar flip-flop door, he saw the superintendent just about to leave—likely for lunch, judging by the determined stride and the slight impatience in his eyes.

Mr. Kalai Mani paused, glanced at him with mild curiosity, and asked, “What do you want?”

Summoning every ounce of acting skill, channeling Kamal Haasan and Sivaji Ganesan in one swift performance, he said, “Sir, I’ve had a bad stomach ache since last night. I can’t sit in class. I really need to go home and rest. I think I need my parents to take me to the doctor. Please, sir, I really need to go.”

Mr. Kalai Mani, clearly weighing whether he could be bothered with this during his pre-lunch hour, raised an eyebrow. “Have you tried eating lunch?”

“Sir,” he responded quickly, “if I even think about lunch, I feel like throwing up.” A slight gagging motion accompanied the words, which seemed to hit the mark.

Not one to linger on the thought of vomiting right before his meal, Kalai Mani sir sighed. “Alright,” he muttered, glancing around the empty office for his assistant. “Ms. Bhuvi?” No answer.

With a resigned shake of his head, he reached for his trusty green ink pen—a sure sign things were getting official—and pulled out the outpass book. “Which class are you in now?” he asked, pen poised.

“7B, sir.”

“7B,” he repeated, scrawling the details onto the slip. Under ‘Reason,’ he wrote simply, “stomach ache.” There was no flourish, no elaboration—just the brutal efficiency of a man who had heard enough stomach-related complaints for one day. He tore the green pass from the book with a decisive rip and handed it over.

But just as the pass touched his fingers, Kalai Mani sir stopped. “How are you getting home?” he asked, clearly not letting the moment pass without one final interrogation.

“Oh, sir, my house is just on Vellala Street. It’s only a kilometer from here. I can walk or maybe take the bus.”

“Take the bus,” Mr. Kalai Mani said firmly, waving him off with a flick of his hand, already halfway out the door and likely thinking about his lunch.

He stood there, holding the outpass like a winning lottery ticket, his heart swelling with triumph. The green slip in his hand was more than just a piece of paper—it was his escape from the cruel clutches of algebra and quadratic equations.

“That’s it, Algebra,” he thought with a gleam in his eye, “you’re done for.”

He hurried back towards the classroom, just as the bell rang, signaling the end of the period. Algebra was officially over, both in the timetable and in his immediate future. The timing couldn’t have been more perfect.

As he reached the classroom, something curious began to happen—his stomach ache, which had been the star of the show all morning, was starting to fade. Perhaps it was the sight of freedom so close, or maybe it was the relief of holding the outpass in his hand like a golden ticket. Either way, he felt a sense of lightness as his classmates began packing up for lunch.

One of them, Raghu, spotted him and grinned. “What? You got an outpass? Man, you’re lucky. This afternoon we’ve got physics. You escaped, but don’t worry—there’s another physics class tomorrow,” he said with a dramatic roll of his eyes.

A few others chimed in, “Lucky guy! Physics is going to be a nightmare. Enjoy your rest!” The envy was unmistakable. Everyone hated physics, and an outpass was as good as winning the lottery on a day like this.

He was just about to pick up his bag when he felt a firm grip stop him. A hand, gripping the strap of his schoolbag, preventing him from leaving. He looked down at the hand, then followed it up to the face of none other than K.C. Anand.

Now, K.C. Anand was a character all his own. Rumor had it he was in the seventh grade for the second time, and not because of any academic brilliance, that was for sure. He had mastered the art of acting like a complete simpleton in front of teachers, throwing them off with his blank expressions and slow responses. But with his friends, he was a whole other person—brave, boisterous, and always up to some kind of mischief. The truth of K.C. Anand’s character was one of the great mysteries of the school. Was he truly clueless, or was this all part of his elaborate performance? No one could tell for sure.

What was certain was that K.C. had an uncanny knack for getting into adventures—funny, crazy, weird, and downright bizarre. If something odd happened at school, you could bet K.C. was somehow involved. The teachers, wise to his antics, warned everyone: “Don’t sit with K.C. in algebra. Don’t partner with K.C. for physics projects. K.C. Anand is a one-man circus, and it’s best to keep a safe distance.” As a result, K.C. always ended up sitting alone, a legend in his own right, creating chaos from the farthest corner of the classroom.

Now, standing there, gripping his bag, K.C. Anand grinned mischievously. “Outpass, huh? So, where do you think you’re going?”

K.C. Anand, without so much as a polite nod, snatched the outpass right from his hand. “Well, my friend,” he said, squinting at the slip as if analyzing ancient scripture, “you look positively dreadful. In fact, I’d say you’re a walking disaster. If you even think about taking the bus, you’ll collapse before the conductor asks for your fare. No, no, no—you need someone to take care of you, someone responsible, trustworthy. And since I happen to live a mere 200 meters from your house, it’s only logical that I be the one to escort you home. What do you say?”

He stood there, momentarily speechless, a situation that rarely happened when K.C. was involved. “But… I can go myself…” he began, though without much confidence.

K.C., of course, was having none of that. Without missing a beat, he reached over and pinched him sharply on the arm. “No, you can’t.”

“Yes, I cannot,” he quickly agreed, mostly out of self-preservation. And just like that, the partnership was sealed.

“I’ll just pop down to the principal’s office and get my name added to this,” K.C. said, already halfway out the door, practically skipping with enthusiasm.

“Wait, wait—Mrs. Aruna’s not here today!” he called after him, hoping that this small detail might halt the steamroller of a plan. No such luck.

K.C. spun around, eyes gleaming. “Even better. I’ll head to the superintendent’s office—ground floor!”

“Superintendent’s out for lunch,” he added, quite certain that this would be the end of it. But of course, this was K.C. Anand he was dealing with, a force of nature immune to the mundane logistics of school schedules.

K.C.’s eyes sparkled with mischief. “That’s my problem,” he said with a wink, and like a whirlwind in school uniform, he was gone.

Now, anyone else would’ve taken at least ten minutes to accomplish this highly dubious task, maybe more if they stopped for some water or a quick chat. Not K.C. In what felt like the blink of an eye—two minutes at best—he came dashing back, looking positively victorious.

“All set!” K.C. declared, waving the outpass in the air like a conquering hero. “My name’s on it! We’re good to go!”

He blinked, utterly flabbergasted. “Who… who signed it?”

K.C. leaned in, smirking like the cat that not only got the cream but also the whole dairy farm. “None of your business. Now, shall we?”

And just like that, they were off. K.C., bag miraculously packed and ready as though he’d never bothered to unpack it in the first place, led the charge down the hallway. As they passed by the classroom, their remaining classmates looked on, half in envy, half in pity. Envy for the escape, pity for the fact that any escape involving K.C. Anand usually meant you were headed straight for some kind of adventure—an adventure that might or might not leave you in one piece.

He clutched the outpass tightly, half in disbelief, half in resignation. He’d gotten his ticket to freedom all right. The only question now was what sort of chaos K.C. Anand was about to drag him into.

With their bags slung over their shoulders and a triumphant air about them, they made their way towards the school gate, where freedom beckoned just beyond the reach of the watchman, a stern fellow who guarded the entrance as if it were the gates of some ancient fortress. As they approached, they noticed a small cluster of younger students lingering near the gate, their eyes darting eagerly from passerby to passerby. These kids were not just hanging around for the sake of fresh air; they had a mission—one that involved convincing any willing stranger to buy them lemon drops or orange drops from the auntie’s shop across the street. The shop, so named because the lady running it was everyone’s “auntie,” was famous for its stash of candies and other minor contraband that weren’t exactly approved by the school’s healthy diet policy.

No sooner had they neared the gate than four of these young hopefuls sprang into action, crowding around them like an impromptu welcoming committee. “Hey, can you get us some lemon drops? Please?” one of them asked, pushing a handful of coins into K.C.’s palm. Another chimed in, “And some eclairs too!” In a matter of seconds, they had acquired a respectable sum of five rupees.

K.C. took one look at the money and flashed a grin that suggested he had more ambitious plans for it than a candy run. However, before he could make a dash for it, they had to deal with the watchman, who was eyeing them with the suspicion of a man who had seen many a seventh grader try to pull a fast one.

“Where do you think you’re going?” the watchman asked, his voice carrying the tone of someone who was prepared to listen to precisely zero excuses.

K.C., undeterred, handed over the outpass with a flourish. The watchman looked at it, then back at the two boys, his brows knitting together. “One outpass for two of you? They didn’t give separate outpasses?”

K.C. launched into an elaborate explanation, weaving a tale so convoluted it involved a miscommunication at the office, an emergency situation, and even a vague reference to the superintendent’s lunch schedule. “You see, sir, it’s a bit of an odd circumstance,” he began, his voice dropping to a confidential whisper. “The superintendent was just about to sign the second outpass when, wouldn’t you know it, he was called away for an urgent matter. Lunch-related, I’m afraid. Very pressing business. You understand.”

The watchman’s expression suggested he understood about as much as a fish understands trigonometry, but he was too tired to argue. “Go, go,” he said, shaking his head as if to rid himself of the entire bewildering episode.

Having successfully secured their passage, they crossed the street and made a beeline for the auntie’s shop, where they fulfilled their duties, handing over the money and receiving a modest assortment of lemon drops, eclairs, and strong mint candies in return. In gratitude, the young patrons threw in a few extra lemon drops as a kind of tip. K.C. pocketed these with a grin, distributing some to his companion with the air of a generous benefactor.

And so, armed with a small supply of sugary loot, they set off towards the bus stand, munching contentedly on the candy and savoring the sweet taste of temporary freedom.

As they made their way towards the bus stand, K.C. was already hatching a plan. Of course, he always had a plan—it was one of his most predictable qualities. “Hey, listen,” he said, turning to him with a glint in his eye, “why don’t we skip the bus and walk instead? It might be better for your tummy, you know. The fresh air, a little movement… probably do you more good than a bumpy bus ride. I mean, it’s just one stop, right? Walking would be A, faster, and B, way less churning for your stomach.”

He opened his mouth to respond, but K.C. had already taken off, striding down the road with a speed that suggested he was late for an appointment with destiny. He hesitated for a moment, stomachache forgotten in the urgency to keep up. Was this a good idea? He was fairly certain it wasn’t. In fact, it was almost guaranteed to be a terrible idea. But with K.C., plans didn’t need approval; they simply required participation. And so, he found himself hurrying along, half-jogging to catch up as they passed the bus stand, heading in the direction of Vellala Street.

As they walked, the prospect of passing the theaters ahead loomed large in his mind. The Abhirami complex was a magical place, an oasis of entertainment situated right between school and home. There were four theaters in the cluster: Abhirami, of course, along with the others whose names he could never quite remember because they were less important than the giant posters that adorned the walls. For him, this was the real attraction. The afternoon sun might have chased most people indoors, but it was the perfect time to see the massive banners without the usual throng of moviegoers blocking the view.

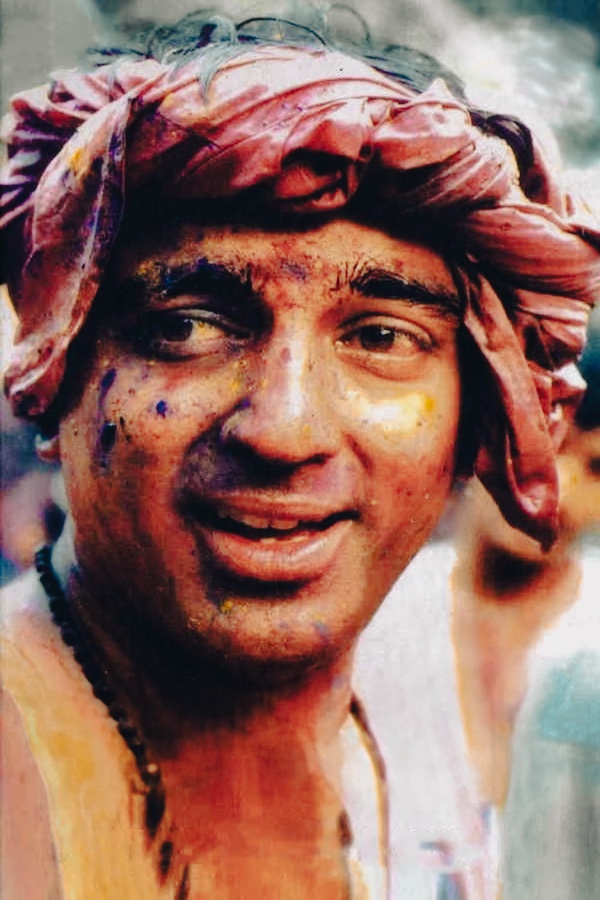

The posters were nothing short of spectacular, plastered across every available surface in bold, eye-popping colors. Each was larger than life, featuring heroes with fists frozen mid-punch, heroines draped in chiffon, and villains with expressions so menacing that it was almost a shame when they inevitably got thrashed by the end of the movie. It was a rare treat—Abhirami was hosting not one, but two Kamal Haasan films alongside a Rajinikanth movie, all at once.

The first was Nayakan, with a poster that showed Kamal Haasan sporting a cloth around his head that seemed stained with blood. It added a gritty, mysterious edge to the image, but he’d later learn that it was merely smeared with colors from a Holi scene, a detail revealed when he finally watched the film. His uncle had already declared Nayakan to be a masterpiece, and the poster’s fierce intensity only heightened the anticipation.

The second Kamal film, Pesumpadam, was even more intriguing. It was a comedy that contained no dialogue—a bold experiment that was already gaining acclaim from Vikatan just a week into its release. He hadn’t seen it yet, but he certainly wanted to. Meanwhile, his eyes kept drifting back to Manithan, the Rajinikanth movie he had already seen and thoroughly enjoyed. He had watched it already and loved every over-the-top action sequence, Rajinikanth’s punches landing as if choreographed by the gods themselves. The energy of that movie seemed to leap off the poster, pulling him closer. The fourth movie, Anand, starring Prabhu, rounded off the list, though it didn’t hold quite the same allure for him.

Seeing two Kamal Haasan films and a Rajini film all playing successfully at the same time was a rare spectacle—a true clash of titans. But his lingering grin, as he gazed at the poster of Manithan, made it clear where his loyalties truly lay.

That’s when it happened. As they neared the theater, they noticed a small crowd gathered just outside the gates, off to the side where the shadow of the marquee didn’t quite reach. The air was different here, thick with a strange mix of sweat, incense, and something less definable—like the lingering odor of damp jute sacks. There was a group of about a dozen men, large fellows who could only be described as adults by the seventh-grade standard, wearing lungis hitched up to their knees, with the edges of their half-trousers peeking out beneath. The lungis flapped with every movement, giving the whole scene a sort of shabby, improvised air.

But that was precisely what K.C. liked about this place—the sense that something unusual, possibly even forbidden, was always just around the corner. He could sense the chaos even before he saw the source. As they moved closer, pushing their way to the edge of the crowd, they could see what the commotion was all about. A man sat in the middle of the huddle—not quite sitting, really, but squatting in that effortless way that only adults seemed to master. His wiry frame balanced precariously over a large wooden block in front of him.

To the side, just barely visible, were two or three roughly assembled boxes, the kind that looked like they’d been put together by hand from leftover materials, secured with twine and perhaps a few dried leaves for good measure. They weren’t much to look at, but something about the way the man kept glancing at them gave the boxes a kind of dark importance. The crowd murmured in anticipation, and he could make out the dull hiss of something stirring within. It didn’t take much to guess what the boxes contained.

K.C.’s eyes widened, a grin spreading across his face. He didn’t say a word, but the look he gave was unmistakable. This was exactly the kind of adventure he’d been hoping for.

K.C. reached the front first, of course. He always did. He had a way of slicing through a crowd like a hot knife through butter—or in this case, like a seventh grader who had no concept of personal space. Meanwhile, he lagged a few steps behind, a growing sense of dread bubbling up in his stomach, which was now churning far more violently than even the quadratic equations had managed. There was a heaviness in the air, like the kind that lingers just before a storm, and his gut instinct was to be anywhere but here. But K.C. kept glancing back at him, grinning and beckoning like a carnival barker. “Here! Here!” he kept calling out, pushing the onlookers aside as though he had some kind of VIP pass to this dubious show.

By the time he stumbled forward to join K.C. at the front, it was too late to back away without drawing attention. The man at the center of it all was now in plain sight, and he was a sight indeed. He wore a black cloth tied around his head—a ragged piece of fabric that looked as if it hadn’t been washed since Indian independence. His lungi hung loosely around his waist, and his shirt, oh, the shirt—it was a psychedelic explosion of colors that might have been considered fashionable two decades ago. The fabric shimmered in a way that suggested it had once been bright and bold but was now just vaguely unsettling.

The man was shouting in a voice that was equal parts menacing and incomprehensible. K.C., naturally, was standing there with his arms crossed, as if he were evaluating the quality of the performance, while he, standing beside K.C., felt every hair on his neck stand up. That was when it struck him—quite literally everyone else there was either a grown man or looked as though they had no pressing engagements besides participating in this shady roadside spectacle. In the glaring afternoon sun, with not a school uniform in sight apart from his and K.C.’s, he realized they were the only boys from the school, which was probably a good indication that they were exactly where they shouldn’t be.

Just then, as if on cue, the man at the center of this ragtag congregation made his next move. With a sudden flourish, he grabbed a long knife—if you could even call it that, given its sorry state—and struck it down onto the wooden block in front of him. The knife lodged itself in the wood with a loud thud, sending a collective shiver through the crowd. The blade was rusted and dull, but the man’s grip on the handle was firm, like he’d just announced his intention to start chopping vegetables, or perhaps, limbs.

“If anybody leaves from here,” he bellowed, his voice now carrying a harsh, almost theatrical edge, “let the evil eye be cast upon them!” His eyes darted around the circle, daring anyone to make a move. “Nobody move!” he added, raising his voice to a pitch that suggested he’d practiced this line many times before in front of a mirror. “If you move, the evil eye will follow you.”

He felt a strange pressure in his chest, a heaviness that seemed to spread from his stomach to his throat, like an invisible hand pressing down. He told himself it was fear—nothing more—but a nagging doubt crept in, an unease that made him hesitate before taking a breath.

The crowd tensed. One unfortunate soul—a man who looked like he had just remembered he was late for something important—began to inch away. The man with the knife shot him a look that could curdle milk. “That person,” he growled, pointing dramatically, “by the end of the day today, will throw up blood and suffer a hundred deaths.”

And with that, he froze. A hundred deaths? What did that even mean? How does one manage a hundred? His brain raced, but the only thought that stuck was that his stomach, which had only just started to settle, was now staging a full-scale rebellion. K.C., on the other hand, looked positively delighted.

The man, with a flourish, pulled open one of the round, makeshift boxes at his side, and there it was—a cobra, coiled and swaying, its hood flaring open like a ghastly fan. The sight of the snake sent a cold jolt down his spine, and just as he was processing that this was indeed a real, live cobra, the man reached for another box and flung it open to reveal a python—a much longer, thicker specimen, its scales glistening like wet stones. Two snakes: a cobra and a python. He could feel his knees weaken and his stomach, already staging a protest, now teetered on the brink of a full-scale revolt.

The man was saying something in Tamil, a strange, guttural slang that seemed to belong to no specific region. It was incomprehensible, but he caught the only phrases that mattered: “You will throw up blood,” “a hundred deaths,” “evil eye.” These words circled through his mind like a dark chant, growing louder and more menacing with each repetition. The snake charmer raised his voice, calling out instructions that sent a ripple through the crowd. “Close your eyes! Put your right hand forward and fold it downwards!” he commanded in a rhythmic tone that made his words sound almost like an incantation. One by one, the men around them complied, hands outstretched and trembling, and, without thinking, he found himself mimicking the crowd’s movements, his eyes squeezed shut, his right hand extended and folded downward.

Beside him, K.C. was doing the same, but when he dared a glance, he noticed K.C.’s hand was shaking more than a little. His face was pale, and even the resolute sandalwood dot on his forehead seemed to be sweating. That was when it hit him—K.C. was just as scared, if not more so. This realization did not offer any comfort. If K.C. was scared, then surely the situation had spiraled far beyond the usual harmless mischief.

The man slammed the knife down on the wooden block once more, the sharp thud making everyone flinch. “Now, the man who tried to run—come to me!” he barked. “Sit down here!” The crowd parted slightly, and a man, meek and shuffling, seemed to stumble forward as if dragged by an unseen force. His eyes rolled, and his body twitched in a way that was either a horrid performance or the real thing—he seemed possessed. He collapsed next to the snake charmer, half-squatting, half-falling, his limbs jerking in a grotesque dance that brought a fresh wave of terror crashing over him.

He was paralyzed with fear, his stomach now in full-on rebellion, twisting and knotting itself into shapes that defied biology. Sweat trickled down his back in a steady stream. He turned to K.C., who was now openly crying, tears spilling from his eyes as he trembled. He wanted to cry too—oh, how he wanted to—but the need to escape was stronger. He glanced around the crowd: some faces were locked in a trance-like state, others were clearly disturbed, but nobody seemed ready to bolt.

That’s when he made his decision. With a swift, desperate wink at K.C., he mouthed, “Let’s run.” K.C. shook his head vehemently, his face contorted in silent refusal. Then the knife struck the block again, and the man’s voice roared out the same dreadful litany: “A hundred deaths! Throwing up blood! Evil eye!” The words drummed into his ears like a relentless war chant.

He couldn’t take it any longer. His stomach clenched so tightly he thought he might collapse then and there. With one final look at K.C.—whose tears were flowing freely now—he spun on his heel, pushed through the crowd, and broke into a sprint, cutting straight through the throng like a wild animal making a bid for freedom. As he dashed past the theater, he could hear the snake charmer’s voice chasing him down the street, “A hundred deaths! Throwing up blood! Evil eye!”

And then he saw K.C., sprinting past him with the speed of a born athlete. Whatever terror had gripped K.C. had now transformed into raw adrenaline, propelling him forward as if his very life depended on it. And perhaps, in that moment, it did. Together, they tore down the road, side by side, fleeing the curses, the snakes, and the man with the knife. But most of all, they were fleeing that dreadful possibility of a hundred deaths.

They dashed past the Meenakshi Mandapam, the marriage hall beside the theater, their feet pounding the pavement as if a hundred deaths were hot on their heels. There was no question of slowing down. K.C. was still crying, tears streaking his cheeks like someone who’d just watched his pet puppy disappear down a well, while he was grappling with an urgent and highly inconvenient need to pee. His mind was a swirl of conflicting impulses: should he be scared, or should he just find the nearest wall and relieve himself? Neither seemed like a good option, so they kept running, not daring to look back.

The road rushed by in a blur of familiar sights and smells. They raced past the Sandhya restaurant, where the rich aroma of chai hung in the air like a tantalizing invitation, mocking them with the idea of a calm they couldn’t afford. They tore past Vivek’s, where television sets and tape recorders peered out from the glass displays as if curious about the commotion. Then came Madarsha, the textile shop, its faded signboard and bundles of fabric lined up like soldiers waiting for orders. But the boys didn’t stop to admire any of it. They could only think of one thing: getting as far away from that snake charmer as possible.

As they veered right onto Vellala Street, the world seemed to change. This was their territory, their zone of safety. The road was pockmarked with the usual potholes, decorated with faded chalk drawings from the neighborhood kids’ games, and cluttered with the occasional cow that had decided to claim the spot as its own. The familiar smell of samosas, kerosene, and jasmine lingered in the air, an odd comfort that reminded them they were no longer in the snake charmer’s realm.

K.C. glanced over at him, and he looked back at K.C., both of them still running. Then, out of nowhere, the two of them burst into laughter—a kind of wild, uncontrollable laughter that seemed to bubble up from the soles of their feet and erupt out of their mouths. It was the kind of laugh that said, “We just escaped a hundred deaths, or maybe we’re still in the middle of one.” Their legs nearly gave way, and they stumbled, half-expecting to roll down the street all the way to their front doors. It didn’t matter whether it was the shock of what had just happened or the sheer relief of having run away—they just laughed, letting the sound fill the dusty air.

By the time they reached G.K.N. Tailor’s shop, they could finally start to slow down. The tailor’s shop marked the perimeter of their world, the safe zone beyond which no evil eye, no snake charmer’s curse, could follow them. They came to a stop, gasping for breath, their sides aching not from a hundred deaths, but from the sprint.

K.C. turned to him, still catching his breath, and asked, “So, how’s your stomach ache?”

“What stomach ache?” he replied. “I feel absolutely perfect.”

They walked the last stretch home, the adrenaline wearing off and leaving them feeling almost giddy with relief. K.C.’s house was a few lanes before his own, a narrow lane lined with houses where children’s voices echoed, and bicycles leaned against walls like exhausted sentries. As they reached the fork in the road, K.C. looked at him, still chuckling, and then leaned closer, his face suddenly taking on the exaggerated solemnity of a street magician revealing a terrible secret. With wide, bulging eyes, and his lips pursed as if delivering the punchline of a ghost story, K.C. chanted in a dramatic, low voice, “Evil eye, a hundred deaths, throwing up blood.” His eyebrows wiggled for added emphasis, making him look like a cartoon villain caught mid-scheme.

It was so absurd that he couldn’t help it—he burst into a fit of uncontrollable laughter, doubling over right there at the fork, K.C. joining in until both of them were gasping for breath.

He laughed and waved K.C. off, then turned to head down his own lane. But just as he reached the gate of his house, he remembered something. With a sudden flourish, he clutched his left side and let out a dramatic groan, “Oh no, the stomach ache! I’m here today because of my terrible, terrible stomach ache!”

And with that, he stumbled into his house, clutching his side with all the drama of a wounded war hero who’d just returned from a battlefield filled with cobras, pythons, and possibly even a curse or two. His hair was askew, his shirt half-untucked, and his face painted with the exaggerated agony of a boy who had narrowly escaped a hundred deaths—or, more accurately, a very vigorous sprint home.

As he limped through the front door, his grandma’s voice rang out from the kitchen, “What happened to you?”

Without missing a beat, he collapsed theatrically onto the nearest bench, gasping out, “Stomach ache, Ammamma… very bad… since last night!”

And then, as he caught his reflection in the mirror—sweaty, disheveled, and still holding his side for effect—he realized the absurdity of it all. He was alive, unscathed, and had managed to outrun the most terrifying villain of all: K.C. Anand’s plans.

But in that moment, it struck him: if he really was going to die from something, it wasn’t going to be a snake charmer, evil eye, or even a hundred deaths. No, the only thing likely to finish him off was this—laughter.

Leave a comment